Language Debt

A few days ago, there was a great conversation on Twitter between James Kyle and Jordan Walke about Reason and JavaScript, and what approach has lead the industry further (sic).

At some point, the conversation evolved to discuss whether it would be better to keep improving JavaScript, instead of switching to a totally different language, to which Jordan answered:

This conversation, and in particular the mention to local maxima, led me to think about how JavaScript has evolved over time, where we currently stand today in the progress line of that evolution, and how programming languages –and their limitations– can affect product teams in profound ways.

📈 Evolution Of JavaScript

The first versions of JavaScript were originally very limited. There was no way to handle exceptions or create function closures, for example.

Over the years, thanks to the efforts made in standardization (TC39), engine implementation teams, and community projects started by individuals like CoffeeScript, Babel or Node.js, many features were progressively added, transforming JavaScript into a mature language that currently powers thousands of products and profitable businesses that provide value to millions of people and other businesses.

However, there are two core language features that for different reasons have become dearly needed for many JavaScript users.

🔒 The Rise Of Immutability

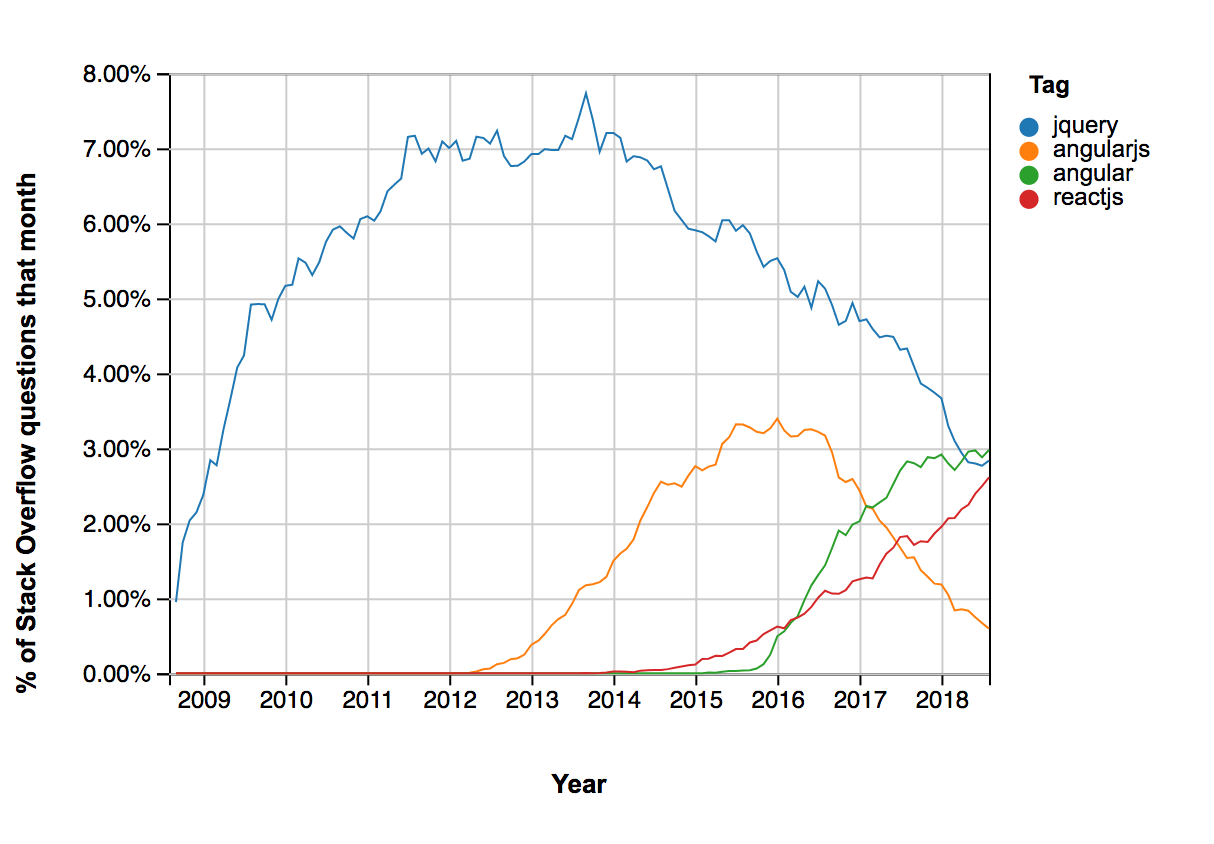

In 2013, Facebook open-sourced React, created by Jordan Walke. It was received with some skepticism, but it is hard to argue its success today:

A view of React growth (from Stack Overflow Trends)

At the time of its creation, there was no language support for classes, so React provided one: createClass. But JavaScript kept evolving, and once classes became part of the language, the React team deprecated createClass and started promoting the idiomatic way.

Apart from classes, the functional nature of React put the spotlight on many concepts that were not that familiar for JavaScript developers at the time. Things like composition, purity, or side effects. One of these ideas was immutability, which is at the heart of React.

React elements are immutable:

Once you create an element, you can’t change its children or attributes. An element is like a single frame in a movie: it represents the UI at a certain point in time.

And props are read-only:

Whether you declare a component as a function or a class, it must never modify its own props.

At the time, mutability was dominant in JavaScript applications: the DOM API is mutable, jQuery kept the DOM as the UI source of truth, relying on mutability to update it, and the only complex data type provided by JavaScript at the time –objects– was mutable too.

But considering the declarative and unidirectional flow of data in React, it became a common practice to use referential checks with immutable data structures instead of structural checks, in order to optimize the performance of complex applications: see “Optimizing Performance: Using Immutable Data Structures”.

In this case, the language did not provide solutions. So a feature that generally belongs to the language domain suddenly became a concern for the language users. How does one achieve immutability in a language that doesn’t provide support for it?

Given JavaScript’s flexibility and fertile ecosystem, several immutable libraries (one, two, three, four) became available over the years. But product teams still need to spend time deciding which library to choose given their needs, which is not always obvious considering how nuanced and complex the subject is. These teams also assume the costs of upgrades and risks of maintenance in case the library stops being developed, or if it ends up not being performant enough for the specific needs of the product.

Which takes us to the second language feature.

🛡 Type Systems

As JavaScript evolved, it became possible to build more complex apps, and the number of mid- and large-sized companies using it increased.

With this growth, engineering teams using JavaScript also got larger, and at some point the lack of a type system became more notorious. A type system would add more guarantees while refactoring, and would make collaboration between engineers in larger teams easier.

As with immutability, the ecosystem came up with solutions to fill the gap. However, implementing a type system is no easy feat, so in this case there were not that many options. Only three ended up appearing, both backed by some of the world largest companies:

- Closure Compiler, by Google –which has type checking capabilities too, besides featuring dead code elimination.

- TypeScript, by Microsoft.

- Flow, by Facebook.

All of them are really powerful, and have helped thousands of teams to scale their apps to levels that otherwise would not be possible, or much less efficient at best. But the lack of a language provided solution puts again a large responsibility on the users of the language, which are forced to make a quite difficult choice.

These teams also assume part of the maintenance costs –upgrades and library type definitions–, and some risk in case the tool they end up choosing ultimately loses traction over time.

The diversity of entities involved in TC39 has drawn out JavaScript evolution, because each standard needs a broader consensus in order to be accepted. But this broad consensus has been in large part the source of its endurance over the years: no single company owns JavaScript.

However, a type system maintained by one company –even as large as Google, Microsoft or Facebook– is arguably riskier than a language with 20+ years of history, driven by a standards committee formed by “engine implementors, developers, a handful of academics and theorists, and Brendan Eich”. Or in other words: TypeScript and Flow are not JavaScript.

Or at least, not yet. Their features could end up being integrated by JavaScript, like what happened before with CoffeeScript and the arrow function. But we don’t know for sure this will happen, and we certainly don’t know when. In this case, it might take some time, as the inherent complexity of a full type system seems to be much larger than the addition of new syntax like the arrow function.

Creating a type system over a language like JavaScript carries some technical constraints as well. Flow and TypeScript were created to remain as close to JavaScript as possible, which turned out to be a great move to incentivize adoption, as they are much less intrusive than the alternatives. But that decision also poses some technical challenges. For example, Flow does not own the compilation process, so it will never be able to apply any performance optimizations during that process. TypeScript gave up type soundness from its conception by design, so one can never be 100% sure that the types you write will type check as expected.

⛰ Local Maxima

Unfortunately, there is no solution in sight for any of the features mentioned above, even at a standard / spec level.

Regarding immutable data structures, Sebastian Markbåge made a proposal back in 2015, but there seems to be no progress since then.

A standard to specify a type system for JavaScript is not in sight either. Brian Terlson, an editor of ECMAScript says in a statement:

Speaking as someone who proposed types for JavaScript in 2014: I do not believe types are in the cards for the near future. This is an extremely complex problem to get right from a standards perspective.

These two features –immutability and type systems– might seem disconnected, but they are both examples of guarantees the language runtime could use to improve performance. Third party immutability and type-checking can’t be relied on by the runtime to improve language performance.

The ceiling of performance optimizations that can be applied at runtime is influenced by these two features working together, but also by others that might seem less relevant at first, like circular dependencies. Elm, OCaml or Haskell for example don’t allow circular dependencies between different modules, which imposes a limitation on users, but also liberates them from the responsibility of removing those circular dependencies as the codebase evolves. It also gives room to the build process to be much faster and incremental.

It has to be noted that the problem is not only language features that might be lacking, part of the problem is also language features that exist today but should be removed. For example, certain optimizations are just not possible when any kind of polymorphism is allowed at runtime. These optimization-blocking features are a big impediment to improve the language too, because there is no way to make progress without introducing breaking changes.

When the architects of a programming language have full control over the type system, data structures and compiler they gain a freedom of design that results in a better experience and performance for the language users. When the ownership of those parts is removed from the language owners, and instead gets fragmented and distributed across the language ecosystem, it becomes much harder to achieve the same experience and make progress.

Ultimately, every participant in the ecosystem ends up paying.

💸 Language Debt

Let’s call language debt the assumed costs (explicit or implicit) by product companies for the maintenance and mitigation of the implications mentioned above. Language debt can be considered part of the classical definition of software technical debt:

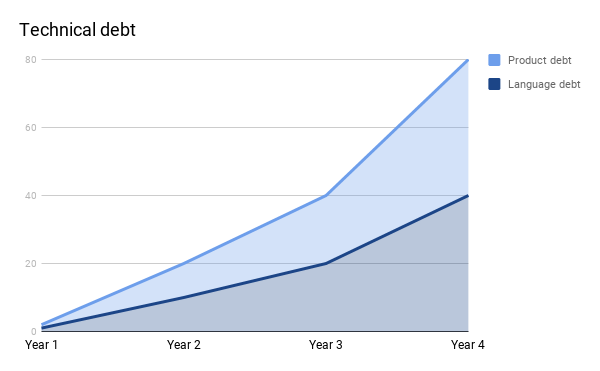

Technical Debt = Language Debt + Product Debt

Language debt has a different nature than product debt:

- Lives at a much lower and generic layer of the debt spectrum than product debt.

- Unlike product debt, the same language debt can be paid multiple times by different companies, teams or individuals (in form of library creation, tooling, long build times, runtime errors, type definitions, versions upgrades,…)

- Language debt grows if no actions are taken –like product debt– as new features keep being added to the product and the size of the team increases.

Examples of activities connected with language debt might be:

- Choose a third party immutable data structures library and integrate it in the codebase

- Choose a type checking tool

- Increase type coverage by adding type annotations

- Remove circular dependencies

- languaRefine the type definitions of a third party library

Evolution of product and language debt over time

❓ “Do We Own Language Debt?”

Every product using any language owns a part of that language debt, larger or smaller, the question is what kind, and how much. In the case of JavaScript, large part of the language debt assumed by its users is due to the features discussed above.

From freelancers, library authors, small startups and huge corporations. Everyone has been obliged to roll up their sleeves and figure out in which ways they could get around those issues as they grew their products, usually reinventing the same solutions, or fixing the same problem over and over. The existing overlap between Flow and TypeScript is the most notorious example of the consequences of such a massive delegation of responsibilities from the language architects to the language users.

So how to identify language debt as part of a product team?

Pseudo-Bikeshedding

One way to identify language debt is to be on the look for discussions around immutable libraries, performance of basic data structures, or type systems. These discussions might feel sometimes like bikeshedding, although it’s not the case at all. The feeling is understandable, because:

- the issues are really far from the actual problem space and business needs of any product company.

- the discussions usually happen between a group of product engineers, not programming language architects: there is a large gap between both disciplines. A counter example would be a group of compiler engineers discussing about UI libraries or first-time user experience in a web application. It can be fun, but it is quite unlikely that anything disruptive will come out of it.

Pseudo-Infrastructure

Another hint that points to language debt is the formation of teams that go through the codebase to increase type coverage, work on the creation or integration of some immutable library, or attempt to remove circular dependencies to increase the performance of the developer tools.

These teams generally include the name “infrastructure” in their name, like Facebook “Developer Infrastructure” team, which was behind the creation of Flow. The purpose of these teams is in essence to pay off language debt, and those efforts should be categorized as such. Doing otherwise will mean language debt is implicitly assumed as any other product need, which won’t facilitate the evaluation of the total size of that debt.

🛣 The Future

Considering all this, what options are available for product teams using JavaScript today? We can circle back to that Twitter conversation between James Kyle and Jordan Walke, and the two main paths that were presented:

- Bet on JavaScript: choose the options that remain closer to the language –like Flow or TypeScript– and fill the feature gaps like immutability with libraries provided by the ecosystem or internal development, hoping that one day the situation changes and they all get eventually added to JavaScript.

- Move on to a compiled-to-JS language: start migrating to some language that offers a sound type system, immutability, performance and other advanced language features. The available options don’t cease to increase and improve: Elm, PureScript, Fable and Reason are some of the languages offering those features, and they are currently used in production by several companies. Of course, there are trade-offs when choosing one of these languages: the costs of writing and maintaining bindings with existing JavaScript code should not be neglected, and the smaller size of their ecosystems increases the risks assumed by the companies betting on them. The pools of available candidates for hire will be smaller as well. This is also language debt that is also assumed in case of picking these languages.

🤔 Ending Thoughts

Even if there are core limitations in JavaScript that have not been solved today, there are more options available to get around them than ever. All of them are valid, depending on the size of your company, your team background, and your product needs.

Also, please note that while the features discussed in the article are very useful, none of them are a hard requirement either! 🙂 A lot of companies and teams have built incredibly powerful products without them.

Regardless what path you decide to follow, I hope this post at least will make easier to identify and account for language debt, in order to make more informed technical decisions about the real costs of the available paths.

One idea is to include “language” in the name of the teams or projects that are in charge of paying it, so the cost of this kind of debt becomes more explicit.

Another idea is to use the two indicators above (pseudo-bikeshedding and pseudo-infrastructure teams) to be more aware when language debt is surfacing, and be able to react as soon as it does, as otherwise it will probably compound over time.

Thanks for reading 🙌 If you have any comments or suggestions, please let me know on Twitter.

Keep shipping! 🚀

Many thanks to Richard Feldman and Jordan Walke for reviewing an early version of this article.